Using Corelight and Zeek to support remote workers

Security teams would benefit from reviewing their NSM data to ensure that only authorized parties are interacting with their remote work...

One of Zeek's greatest strengths is its ability to deeply inspect packet streams that are fed into it. It is adept not only at identifying network protocols but also parsing them to extract large amounts of useful information. There is another strength that is often overlooked: Zeek not only extracts information from individual packets of network sessions, it also provides a very flexible and useful way to track state across the lifetime of network sessions. This is particularly useful when examining network protocols such as Server Message Block (SMB) that rely on the endpoint devices to track the state of their conversation.

To illustrate this point, here is a Zeek script for detecting attempts to exercise the PetitPotam exploits. We will walk through how this works in this blog post.The PetitPotam exploit offers an opportunity to illustrate the power of Zeek for tracking the state of network conversations over their lifetime. PetitPotam abuses EFS DCERPC functions to trigger an NTLM relay attack that can be used to gain elevated privileges in a Windows AD domain. The exploit takes place inside of an SMB session that involves several phases that must be tracked: the negotiation of the session’s parameters, an authentication, one or more RPC function calls, and their matching responses. As a result, detecting this exploit requires tracking the state of several network protocols over the lifetime of their sessions. There is no single packet or portion of the ongoing conversation that contains everything necessary for detection.

First, let’s examine the different parts of a successful PetitPotam exploitation, and then we’ll see how Zeek tracks the state of the network protocols for us to enable the detection process.

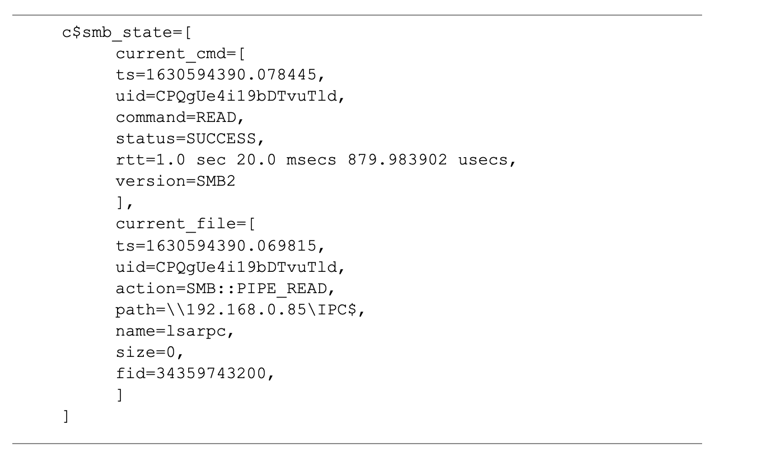

PetitPotam exploitation works by abusing the lack of sufficient permission checking when calling EFS DCERPC functions on remote Windows systems. In most cases, calling a remote DCERPC function occurs over an SMB session, so each exploitation starts by negotiating the SMB session’s parameters. Zeek takes care of tracking the state of each SMB session and its associated TCP session for us out of the box by storing much of what it knows for later use. This information is stored inside of the record that Zeek keeps for each network connection that it sees. By tradition, the connection record is referred to by the variable c, and additional information about each connection is stored in sub-variables delimited by the $ operator. For example, additional information about the current state of each SMB session is stored in c$smb_state. Figure 1 shows a small portion of the information that Zeek has recorded about an SMB read operation from \\192.168.0.85\IPC$ (Note: this snippet is paired down for readability; there is a lot more information available in c$smb_state). What you need to know is that Zeek is tracking this type of information for us across the lifetime of each SMB session. As each SMB session progresses, Zeek will add or update values to this subrecord so that it represents a summary of the SMB session’s current state.

Figure 1

The next step in detecting a PetitPotam exploit is to dissect the DCERPC function calls that ride on top of the SMB session, and look for signs of someone attempting to trigger an NTLM relay by making an EFS function call. Again, Zeek takes care of most of these details for us by treating DCERPC as just another network layer above SMB. Also like the SMB sessions, Zeek stores state information about the current DCERPC call or response in several places within the c variable. In the case of DCERPC, this state information is stored in c$dce_rpc, c$dce_rpc_state, and c$dce_rpc_backing.

Unfortunately, the DCERPC protocol’s multiplexed nature makes it more difficult to analyze than other protocols. Function calls and responses do not need to be sequential; they can be interleaved and sometimes even out of order. That is, inside of a single SMB session, there can be more than one DCERPC function call active at the same time awaiting a response. To add to the complexity, DCERPC requires a separate bind action within the SMB session that selects the family of functions that will be called. This means that a single remote function call will require a bind action, a function call, and a response, all of which will appear in separate portions of the TCP session.

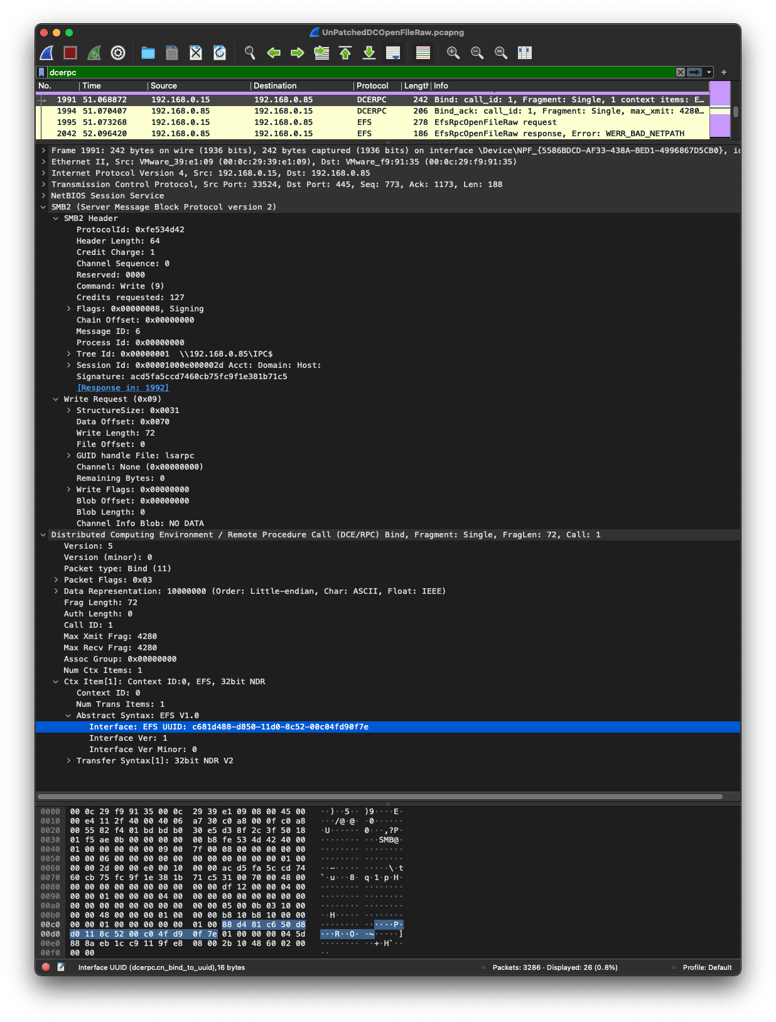

Thankfully, Zeek tracks all of these details for us. Consider Figures 2, 3, and 4 below which show the bind, call, and response sequence of packets that exist during an attempt to trigger the PetitPotam exploit. Prior to this, the attacker (192.16.0.15) has negotiated an SMB2 session with the victim (192.168.0.85). In Figure 2, the attacker binds to the DCERPC endpoint c681d488-d850-11d0-8c52-00c04fd90f7e, which is associated with the Windows Encrypted File System DCERPC functions (see the line near the bottom of Figure 2 that is highlighted in blue).

Figure 2

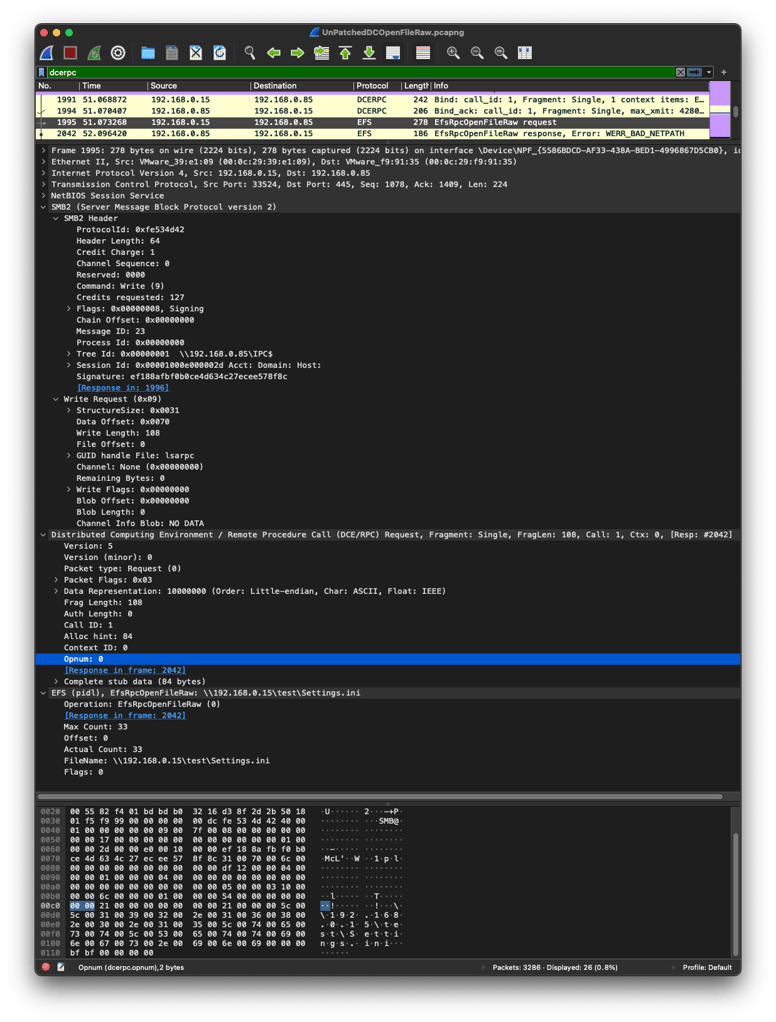

Next, the attacker tells the victim that it wants to call the EfsRpcOpenFileRaw function, which has the operation number 0. This is visible as the Opnum value on the line near the bottom of Figure 3, again highlighted in blue.

Figure 3

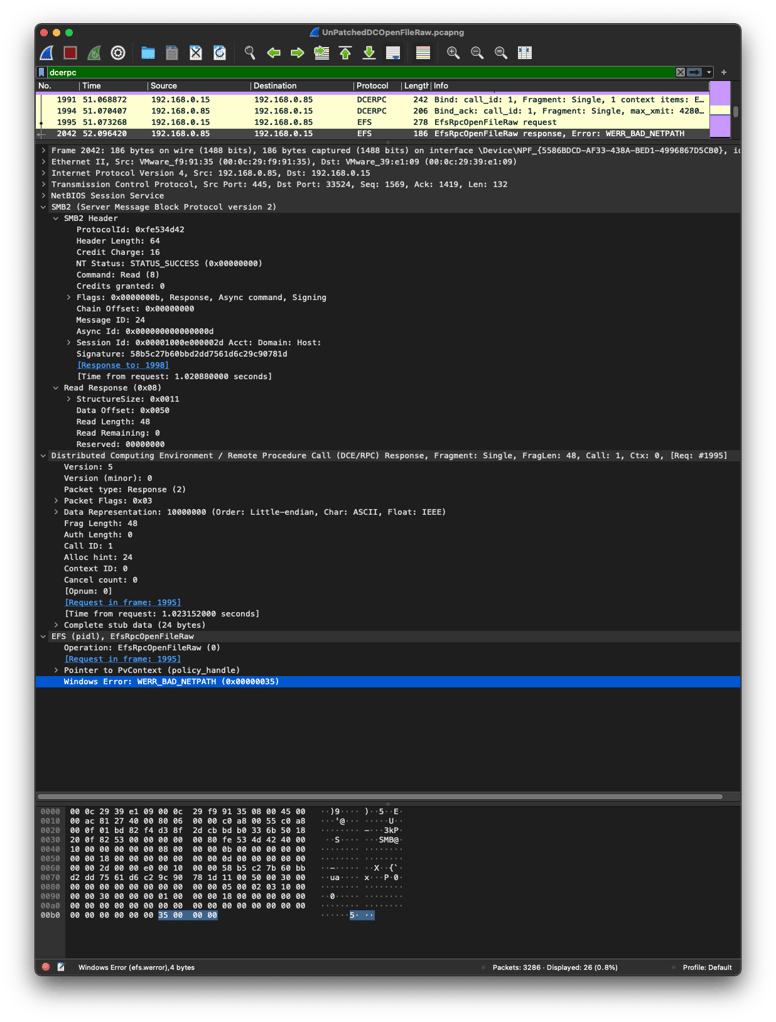

Finally, when the victim host has finished executing the EfsRpcOpenFileRaw function, it sends back a response with a return value, which in this case is 0x00000035, per Figure 4.

Figure 4

The only guarantees offered by DCERPC are that these three calls will be in that order within a single SMB session. There may be other function calls and responses interspersed between them which could result in the different stages of the PetitPotam exploit being more broadly spread across an SMB session and intermixed with other, legitimate, SMB operations.

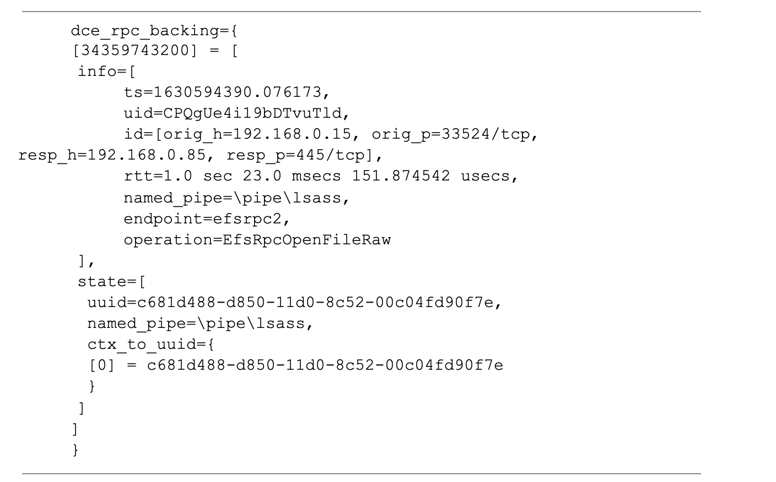

Zeek, however, takes care of keeping track of the state of each DCERPC bind, function call, and response for us out of the box. By the time the response to the function call is finally seen on the network, Zeek has bundled up all of this information for us in c$dce_rpc_backing. See Figure 5.

Figure 5

The only part still missing is the index number (34359743200), which is the reference number for the open DCERPC call associated with this response. Zeek again takes care of the tracking details for us by passing this value to the dce_rpc_response event as the value of the argument fid.

We now have everything we need to detect attempts to trigger a PetitPotam exploit. Since Zeek has taken care of the task of tracking and collecting information through the lifetime of the DCERPC session, we only need to capture DCERPC response events by writing a handler for the dce_rpc_response_stub event. Using the fid argument passed into the event handler, we can extract the DCERPC endpoint UUID, and the name of the function called from the saved state. Then, by comparing the DCERPC endpoint against those that are abused by the PetitPotam exploits, and by examining the function’s return code we will notify the analysts in near real time that a possible exploit attempt has occurred and whether it appears to have been successful or not.

By Paul Dokas, Director of Corelight Labs

Security teams would benefit from reviewing their NSM data to ensure that only authorized parties are interacting with their remote work...

Learn how to detect the CVE-2021-42292 exploit, which relies on Excel fetching a second Excel file, through behavioral tricks.

A growing number of defenders use two SIEMs. This post explores why and whether XDR platforms will evolve to to become full threat hunting solutions.